Reality ? Reality ! - Šimon Brejcha X Martin Velíšek

18 / 04 / 2018 - 05 / 07 / 2018

Cermak Eisenkraft, Pop Up Gallery Smetanovo nabrezi 4.

Authors: Šimon Brejcha, Martin Velíšek, Tomáš Zapletal and David Železný

Texts for the exhibition: Kristian Vistrup Madsen, Eva Bendová, Tomáš Zapletal, Šimon Brejcha, Martin Velíšek

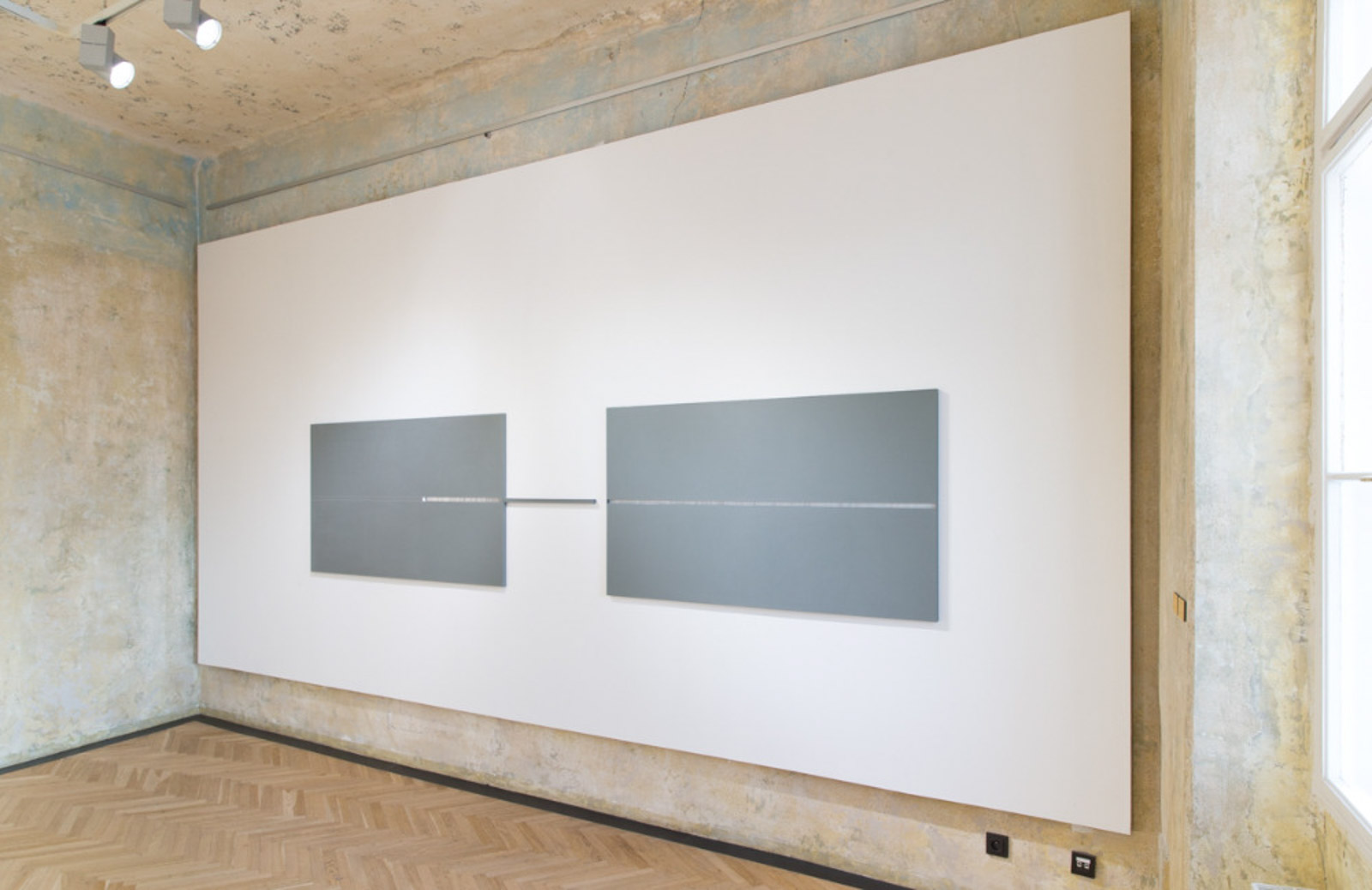

Installation

|

A seat at the table: On the art of Šimon Brejcha and Martin Velíšek

It is a little known fact that the word chair derives from the word cathedral. This has to do with the cathedral being a seat of power, influence and reverence, in the same way as we still talk of the chairman of a board. In fact, until the renaissance, in Europe, chairs were hardly used outside of ecclesiastical settings, and in the royal courts, as thrones. People simply sat on benches, on chests or on the floor. Although in modern times we know the chair as among the most pedestrian of items, for centuries it was synonymous with authority, and individual seating options were considered, not only lavish, but entirely unnecessary.

Let’s look again, then, at Martin Velíšek’s photorealistic chair paintings. What do they mean? It is no coincidence that it was in the renaissance – also the age of the portrait painting – that the chair became a more commonplace item: This era gave birth to the very the notion of the individual. As such, the chair is not the empty or mundane signifier one might assume, but a carrier of information about how we see people as distinct from one another; not seated in a row, as masses gather in a stadium, but separate and different, as each chair is separate and different. Each chair a kind of portrait: A light brown cushion and backrest are held by a curvy black frame. This funky chair looks like it was commissioned for a public building in the 1970s. The lobby of a library, perhaps, flanked by a large potted plant. A simple white wooden specimen spent decades in the same kitchen absorbing the smells and the fumes. Now breathing them back out as splinters in its surface, the brittle construction appears the survivor of a battle with time. Due to Velíšek’s incredibly skilful rendering, the chair paintings function as highly detailed testimonies to the existence of the item in question. In so doing, they build on a tradition of meticulously accurate interior paintings going back to the 18th century. Back then – not unlike the status previously awarded the chair – the purpose was partly to flaunt one’s wealth and good taste, and partly, still before photography, preserving the memory of a particular decorative style for future generations. But in Velíšek’s painting, the light blue plastic upholstery of a sofa is breaking off like dead skin. This is clearly not a status object, but a story about how things are used and expire – a trivial piece of material history, which, in the heyday of interior paintings, would hardly have been worthy of oil and canvas.

But by the late 19th century that genre would also move away from its emphasis on documentation to something more intangible. The often empty, alien interiors of Vilhelm Hammershøi, for instance, are underscored by an existential sombreness similar to what we see in Velíšek; solitary furniture speaking to the fundamental loneliness of life. Another similarity to at least some of Hammershøi’s work is that Velíšek’s chairs appear completely without context, as if on blueprint, not quite in the world, but still in the making. This adds a meta-layer to his work, no longer just about what the chair itself signifies, but what it means to represent it. This is further accented by the large canvases, which allow Velíšek to render the furniture in their actual size, lending them a trompe l’oeil effect. Since the beginning, this has been a familiar trope of interior and architecture painting – one that blurs the line between the image and what is outside of it, or, put differently, between the two- and the three-dimensional. A different series of works by Velíšek venture deeper into this territory, inserting real furniture components or materials, such as staples, wheels, or sliding tracks, into white canvases. Seen as an elaboration on the chair paintings, these works have abandoned depiction in order to approach “the thing itself”. Here, the question posed by Velíšek is an ontological one: what makes a chair, or, indeed, a painting? What is the nature of its existence? This is a question of the difference between being and representation – one very much at the core of Šimon Brejcha’s practice as well.

One of the Czech Republic’s most celebrated graphic artists, Brejcha’s works are to be seen, not in relation to the history of painting, but to the tradition of pressure and imprint – an entirely different mode of depiction. Or rather, not depiction at all, but trace-making: like the handprints at Hollywood’s Chinese Theatre, not the representation of hands, but an attestation to their being. The series of prints titled Modul (Module) takes as its starting point a grid cube constructed by Brejcha out of wooden sticks. Running the structure through a press, its shape and texture is etched into paper, and the contours filled in by Brejcha. The wooden cube can then be expanded, repeated and made to form different patterns, such as in the series Kótování (Dimensions). A dimensions differs from a representation in that there is a direct relation to the thing-proper that has not been subject to interpretation; Brejcha’s prints are engraved by the wood itself, not mediated by his artist’s brush. However, still, there remains the possibility of misquotation: of moving away from the original object slightly and naturally with each repetition, each new imprint. In this way, Brejcha develops his own language in which the significance of each thing is determined by its difference from the things that came before and after it. According to the semiotic theory of Claude Lévi-Strauss, this is how all language works: a chair is defined by its not being a stool or a seat or a recliner. Brejcha’s graphic universe expands by this logic from a basic structure, through experimentation and reiteration, into anything at all. Some look like scientific studies of moss, lichen, or insects, others like architectural drawings for modernist cities, only far too chaotic for this world. Whichever real and tangible object formed the basis of the work, it was not typified by Brejcha, but always already, and this is his point: the individual specimen means nothing without its flock. A row of paintings by Brejcha of amorphous white figures from the 1990s – the two-dimensional cousins of his Hans Arp-like sculptures – similarly suggest nature’s disregard for boundaries: these shapes could go on forever. This brings us back to the chair as a conceited attempt to distinguish any one entity from a mass. Brejcha too has painted a chair: small, in every sense, and, like Velíšek’s, lonely. But lonely precisely as all other things, and for that reason connected to them. A semiotic field of chairs; the same but different.

Kristian Vistrup Madsen

Vernissage

|